“The Messy Years”: What a mid-life career change feels like

In 2010, at the age of 37, I decided I needed a change of course. This was not a sudden or novel thought. I had been ruminating over it for a good 5 years, and my body had been ‘working on it’ for decades. I had joint pain since my teens, and had the feeling my body was waking up every morning saying :

No No…!

Uh Uhhhh….!

You are NOT going to put me through this for the rest of our time on earth together.

What did this look like in practice?

I couldn’t fully feel some of my fingertips

I had chronic pain in my left-hand index finger and persistent right-side ‘tennis elbow,’ sometimes radiating down to my wrist.

I was in generally poor health, severely anemic. I’d get exhausted after 30 minutes of practice and need a ‘coma-death-nap.’

Standing up quickly meant losing vision for five seconds, standing there swaying like a sleepy cow. (Not that cows are blind, but you get the idea.)

This once happened during a bow on stage. I stood there, swaying, blind. I wish I had just passed out completely—it would have explained away the bad playing and been VERY dramatic! Swoon…

This is a woman in possession of half her blood

In 2008, my doctor sent me to the emergency room for a blood transfusion, stating that I had half the blood reserves of a normal person.

A week in the hospital led to a fairly common autoimmune diagnosis: Celiac Disease. I was so desperate for an explanation that I latched onto it. Celiac was the reason for everything!

If I didn’t eat evil bread, I’d snap back into shape.

Evil Bread…

For the next two years, I stuck to that narrative. And sure enough, many things did improve.

But the chronic pain remained. The lack of sensation in my fingertips was still there.

Performing often had become traumatic. It’s a strong word, but I use it with intention. Imagine slogging through practice in chronic pain, unable to fully feel your fingers, and not knowing if your hands would betray you on stage—which they did, with increasing frequency. The career of a musician is hard enough as it is. But when there’s no joy in practice and terror in performance, why do it?

Deciding to stop was an extremely long and difficult process. In hindsight, the financial precarity, lack of future prospects, and constant hustle for work were reason enough to switch careers. But since I had been on this track since early childhood, I needed the extra push from my body to finally cross the Rubicon.

The Rubicon Moment

After a particularly difficult concert in 2010, I was complaining to those around me: “I can’t do this.” “This is terrible.” I suddenly heard myself. And I didn’t really like the person doing the complaining. If I kept saying, “I can’t do this anymore,” I needed to follow through with some kind of action. So, I threw everything overboard and applied for a Bachelor’s program in Psychology at Berlin’s Freie Universität.

(Please read on below for a call for more incremental, gentle, and gradual change processes…)

Leaping into the Unknown

I didn’t exactly choose psychology with great deliberation. I would have loved to study literature or philosophy, but after 15 years as a freelance musician, psychology seemed like a more practical path. Plus, a lot of the readings were in English—score!

Psychology is protected by Numerus Clausus, a system in German universities that strictly limits student admissions based on academic merit. To this day, I’m not sure why I was accepted. My high school grades were not stellar, and suddenly I was surrounded by A+++ Brainiacs who were half my age.

Studying statistics in German left some permanent scar tissue on my brain.

The learning process was experimental at best—attempts, failures, new attempts. Fortunately, I found a group of other women in their 30s who were also switching careers, coming from film, business, and healthcare. We called ourselve “Die Alten Geister” (“The Old Souls”) and pooled our resources to hire a statistics tutor—a brilliant 19-year-old redhead who aced Bayesian inferences and Stochastics and tried, through sheer repetition, to make our middle-aged brains also understand. I also discovered that some textbooks are terrible teachers, and that statistics explained through comedy videos and light-reading made a world of difference. Eventually, I scraped by with a mediocre grade.

And… Did I Mention?

My biological clock was pounding. Having a child as a professional musician had felt impossible. Having a child during a career transition felt even more impossible. But time was not on our side. Our daughter arrived in September 2011, and I took a semester off. Those were some of the most magical months of my life. At least, that’s how I remember them. There were, of course, difficulties, but this profound bracket in life —only attending to a precious baby—was glorious.

After that, baby came with me—to seminars, to concerts, even to Orléans, where I was on the jury of a competition. Thank goodness for a spouse who was an equal partner. This is us backstage at the Concours international de piano d'Orléans, me wearing a scarf. Not for fashion, but to cover the leaky boob stains that showed up as a result of supplementing breast milk with formula while I was working.

The Messy Years

It took me five years to complete a three-year program. That’s okay. I was studying, raising a child, and teaching piano to finance the whole thing.

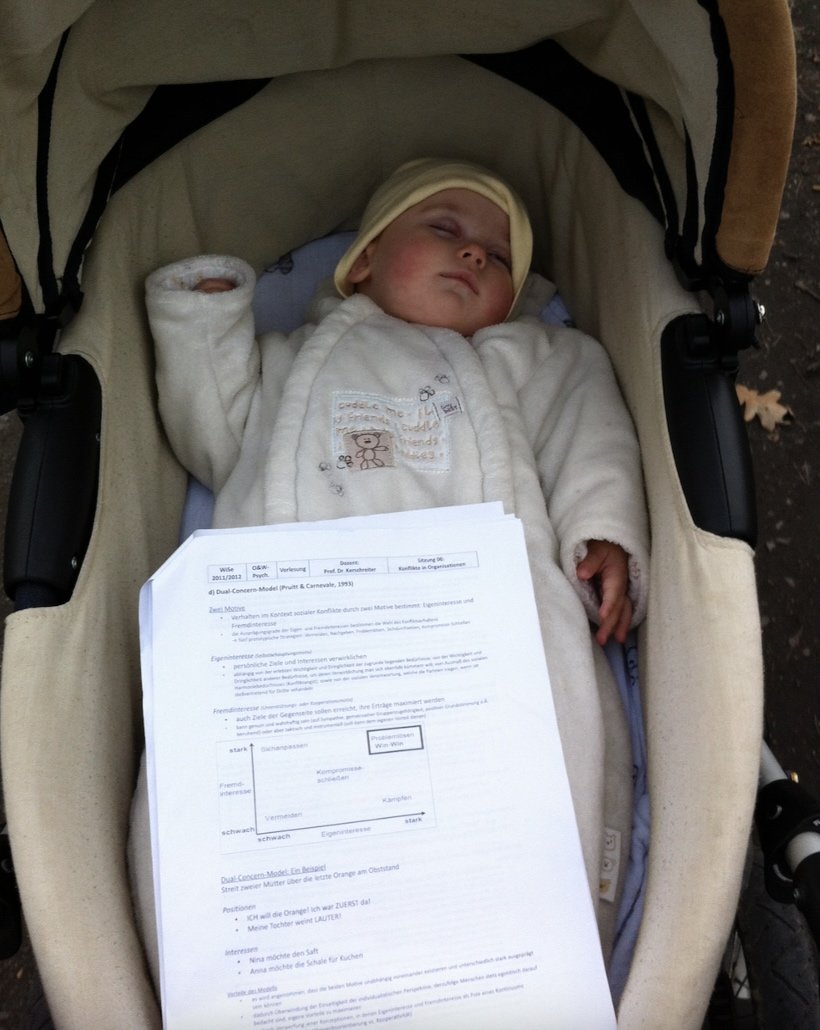

This picture seems emblematic of that time:

It was messy. I made mistakes constantly. Often, I moved forward without a clear plan. This approach isn’t recommendable or particularly good for one’s mental health or well-being, but it certainly was human.

I finished my degree in 2015, after we had just moved back to the USA. My diploma arrived in the mail. I’m pretty sure I didn’t take the time to celebrate. Again—not recommendable, but fitting for those ‘messy years.’

Lessons from ‘The Messy Years’

I could have done it differently. I could have planned a smoother transition, taken time to rediscover who I was outside of the Piano-Identity, and chosen my field of study more deliberately. I could have eased into change rather than throwing everything overboard all at once. I would probably advise my clients to take small, incremental steps using SMART goals—Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound—to reduce stress.

But life isn’t an elegant sequence of SMART goals. Life is messy, and we humans are messy. Sometimes change isn’t a well-plotted journey—it’s a leap, a stumble, and a scramble to regain balance.

In hindsight, I didn’t really cross the Rubicon—I tripped and fell into it, flailed about, and eventually dragged myself onto the other shore, soaking wet and slightly bewildered.

I’m glad I made it.

Sometimes the only way forward is through the mess.

A toddler in the Freie Universität

A day at the Freie Uni in 2012, photo taken by one of “Die Alten Geister” group…