Musicians’ Performance Anxiety: The (nervous) Elephant in the Room

If one writes a series of essays on music psychology, the most obvious topic is Performance Anxiety, right?!

RIGHT ?!?!

Yes, and it’s one of the most common themes in my work with clients.

But, I don’t want to write about it.

Why?

Because of its nature: It’s slippery. It’s elusive. It’s shows up differently in every single person I work with. It’s resistant to generalizations.

Performance Anxiety can feel like a trickster, a conniver, and shape-shifter. It’s shared by a majority of people in the music industry, but it feels like it’s carried alone by each individual musician, and mostly in seclusion and secrecy.

And man, it can be heavy… (like an elephant… an elephant on stage).

Please, no ‘Tips and Tricks’

What I don’t want to do is give a series of ‘tips and tricks’ to cure performance anxiety.

If performance anxiety is consistently a disruptive factor in performance, it’s probably a well-grooved feedback-loop by now, strengthening and deepening with each repeated performance.

‘Tips and Tricks’ may provide an initial balm that lightens the sense of perma-anxiety and brings about an illusion of control over the process. But ‘Tips and Tricks’ most often don’t seem to really get down to the core of the issue and provide any meaningful impulses for challenging and changing the anxiety loop one is trapped in.

The contributors to performance anxiety may be deep, going back to childhood: experiences with parents, care-givers and teachers. The contributors to performance anxiety may be systemic: musicians working in fields with limited resources and few opportunities for advancement, in which it’s easy to identify with the (unhelpful) maxim : “You’re only as good as your last performance”. The contributors to performance anxiety may even be evolutionary: evoking our ancient and primal fight-flight-freeze instincts.

Considering that it took a lot of time, a lot of personal (not to mention evolutionary) history, and a lot of specific inputs from people in your social milieu to contribute to your own personal performance anxiety, it seems disrespectful for me to dispense one-size-fits-all fixes.

We all know that the good and healing stuff takes time and personal engagement.

So please view what’s coming as an experimental field where ideas can be tossed around. Take these ideas back to your practice room and onto the stage and see how they resonate within your own experience.

Meeting Performance Anxiety where it is

It is possible to come to terms with performance anxiety.

I’ve witnessed it many times.

I am reluctant to use language like “overcome” or “defeat” with regard to performance anxiety, because these terms evoke the image of a fight, and what we’d be fighting is ourselves, or better said, a shadow side of ourselves.

It may not be such a helpful goal to want to banish or exile performance anxiety. There are other options: one can befriend it, one can collaborate with it. One can tame it, if that seems like a fitting metaphor.

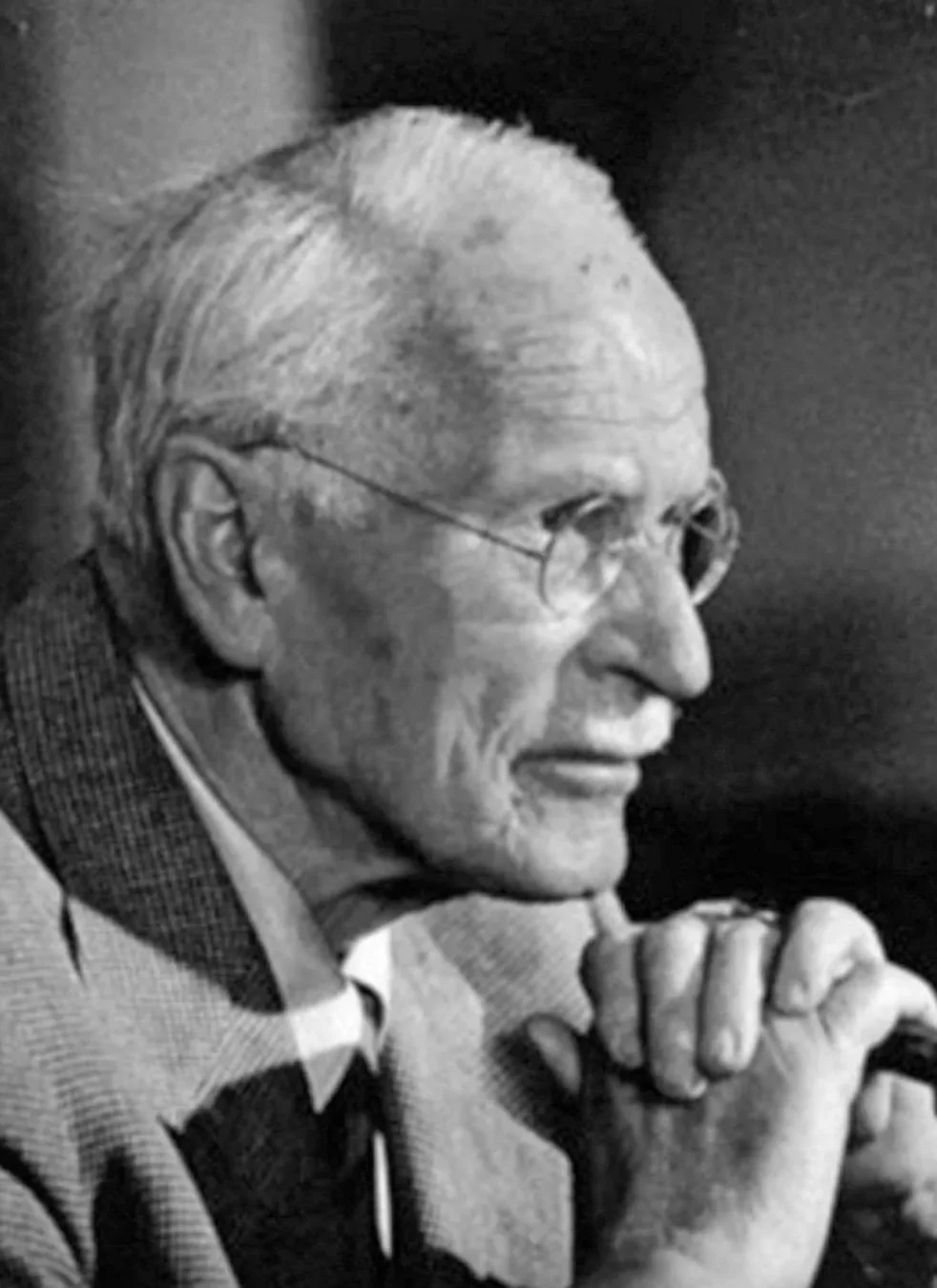

Performance Anxiety may be the musicians’ equivalent of Carl Jung’s concept of the Shadow Self.

“Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is.”

Carl Jung

Jung writes: “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious. The latter procedure, however, is disagreeable and therefore not popular.”

In the spirit of ‘making the darkness conscious’, let’s explore Musicians Performance Anxiety in relation to other forms of anxieties and mental health challenges.

Dianna T. Kenny, a leading researcher into Music Performance Anxiety (MPA) identifies three expressions of Music Performance Anxiety:

Drawings of Jean-Jacques Sempé

1. Anxiety that matches the high-stakes nature of the musical task, and is specifically connected to music performance. A lot is depending on this performance, this audition. You’re going out there and showing the world the years of investment and engagement you’ve put into your art, your craft. Of course you’re nervous. You’ve worked your butt off for this. It would be a bit odd if you weren’t!

2. Performance anxiety that goes along with other forms of social anxiety: you tend to experience anxiety in many situations in which you perceive yourself as being evaluated, judged and scrutinized by others. This anxiety could find its way into musical performances, but could just as likely be present in public speaking, dating, meeting new people, etc.

3. Performance anxiety that’s deeply interwoven with other mental health issues such as depression and panic disorders. Here, performance anxiety shows up as one symptom within a web of many psychological and emotional vulnerabilities.

Below are some quotes about well-known artists’ experiences with performance anxiety.

“One of the most important gigs I ever did was a 1987 concert called “A Tribute to John Coltrane.” I was onstage with Dave Liebman, Jack DeJohnette, Eddie Gomez, and, most important, Wayne Shorter. It was a live, open-air concert in front of 22,000 fans at midnight. The show was recorded for audio and video. There was no possibility of doing a second take. The pressure was tremendous, and I was excited to be onstage that night with those guys. Part of the thrill of that performance was playing for the first time with Wayne Shorter. So I had a lot to deal with. Did I get through it? Yes, and I was very happy with the result, because I liked the pressure and rose to the occasion. Like they say, pressure makes a diamond.“

Richie Beirach, Pianist

“Right before I go on stage, it’s not my favourite moment to tell you the truth, there’s the nerves and anxiety and trying to get into that zone – which inevitably happens once the music starts. Once the music starts and I start playing, I wouldn’t say I become a different person because it’s really getting in touch with who I am, you’re exposing yourself in a very vulnerable way which is I think one of the gifts that you need as a musician. You need to do that unselfconsciously and be able to do that in front of lots of people.”

Joshua Bell

At 9, before performing a Mozart concerto, she knelt down and thought, “If I hit one wrong note, I’ll die.” That sense of perfection stayed with her…“I always doubt,” she says. “I’m always groping. If you’re too pleased with what you’ve done, or you get into a routine, that’s the worst. Sometimes I go out on a limb, so it doesn’t happen.”

On Martha Argerich

"I get shitty scared. One show in Amsterdam, I was so nervous I escaped out the fire exit. I've thrown up a couple of times. Once in Brussels, I projectile vomited on someone."

Adele

“Nerves and stage fright before playing have never left me through-out the whole of my career. Can you realize that at each of the thousands of concerts I played at, I felt as bad as I did on that first occasion?… The thought of a public concert always gives me a nightmare.”

Pablo Casals

“She loved singing and playing to family and friends, but as the gigs got bigger, so did the pressure, highlighting the fact that she wasn’t a natural performer. As Amy was outwardly so confident, no one imagined that inside she harboured a fear of being onstage, and that as she played in front of ever-increasing crowds, the fear didn’t go away. Over time it became worse. But she was so good at concealing it that even I wasn’t aware of how hard this was for her. Quite often, during a song, she’d still commit the cardinal sin of turning her back on the audience.”

On Amy Winehouse

These quotes show a range of responses to the evolutionary processes evoked by a performance situation- fight, flight, freeze, with varying stress loads to the nervous systems of the artists. Stress in performance is not the enemy. The world would be a poorer place if musicians treated the stage like a cozy bathtub.

But performance anxiety can be massively destabilizing for many of us.

What to do?!

Let’s explore some kinds of things that might be part of a psychological intervention working on debilitating performance anxiety.

I can group them into four categories:

Cognitive Processes

Somatic Resources

Musical Preparation

Pharmacological assists

Cognitive Work:

Reframing, Self-Talk, Engaging with the dreaded Anxiety

Could you imagine that your performance anxiety is not evil with an explicit wish to destroy you?

Could you imagine that it is a (probably unconscious) part of you that has been assigned the task of keeping you safe? These are examples of Reframing: Taking unhelpful thought habits and turning them on their heads.

If you were to personify your own Performance Anxiety, what would he/she/it look like? Is it possible to take it out of wherever it sits (the pit of the stomach, the heart, the throat) and have a talk? What is it trying to save or protect you from? Does it think you’re in danger? Or is it just mean and takes pleasure in watching you trip up and humiliate yourself? What does it need? What does it sound like? Are there any resemblances in the tone of its voice that remind you of anyone (a teacher, a parent)? Getting to know your performance anxiety, sometimes conceived as an inner critic, can turn he/she/it from the Hulk into Baby Yoda.

Exploring self-talk

For many clients, self-talk is their go-to method for addressing the inner critic: They inwardly repeat ‘mantras’ during performances: “I’m good enough”, “I have the right to be here.” Or they might follow a strict code of self-directives: “First do this and then that”, “Smile!”, “Grab that high note!”, “Shoulders down!”. In my experience, these ‘self-talk’-methods taking place during performances are limited in their effectiveness and can often backfire. I believe that the reason for this backfiring may be that one is operating on two contrasting brain systems, pitting cognitions (the “I’m good” or “Do this!” thoughts) against raw emotions (“You rotten loser!!!” or “Get me outta here!!!!” (…if they are even verbal at all and not just blazing emotions)). It’s an unequal match-up between the intellectual prefrontal cortex, and the torch-and-burn amygdala, the deep-seated home of our primordial fears.

Because the primal anxieties are dripping in emotions, it seems that pure thoughts are not up to the task of dissipating or transforming the emotional energy. In this regard, mindfulness practices, preferably engaged in over long periods of time, seem to have more efficacy with emotional regulation in the face of overwhelming emotions. Mindfulness practices can take place on the meditation cushion or in the practice room. At heart, these practices can help us metabolize overwhelming emotional content, regain presence in our body when it seems to be galloping off like a wild horse, and hone in on the ‘good stuff’: the flow, the presence, the magical and mysterious aspects of performance that so many describe as ‘the zone’.

2. Somatic Resources

Well, just to repeat myself, mindfulness practices can anchor raging thought patterns and absorb them into a receptive body, so these practices can also be viewed as ‘somatic’(body)-based interventions for performance anxiety. They function best when incorporated into a daily practice ritual and are not just whipped out when one is already on the stage.

Many musicians have experimented with ‘grounding’ during performances when anxiety threatens to overwhelm: locating the floor, the seat, the contact points. If the anxiety is showing up in the fingers as an uncontrollable tremor, some find that focusing on another part of the body (such as the feet) helps to distract the mind from over-focusing and panicking as a result of the altered physical sensations in the fingers. In these cases, it seems that the act of hyper-focusing is the problem, even more than the altered physical sensations due to shaking, sweating, and a racing heart. The over-active mind, which is desperately seeking a place to deposit its anxiety, can be assisted by the body, which works to take the lightening bolts of nervousness and put them into the ground, where they might even be able to provide some good performance energy.

Sometimes performance anxiety isn’t really anxiety at all, but is rather your body stating (shouting) that it’s not feeling supported. Sometimes working with technique coaches can do wonders for developing more of a sense of groundedness. Some musicians have found that somatic practices such as Feldenkrais Method, Alexander Technique, Body-Mapping, Yoga, Qi Gong, and many other wonderful body-based practices helps them to alleviate their performance anxiety.

3. Musical Preparation

Sometimes performance anxiety is your body just shouting at you because it knows that you haven’t really integrated the music into your whole system. Especially for those who perform from memory, you might be engaging in one form of memory, but neglecting another. There are so many ways to absorb music from the page into the body: through the physical (muscle) memory, through audiation (inwardly hearing the music), through an deep understanding of the compositional framework (thinking like a composer), through visualization of the score, through mnemonic practices. We tend to get into ruts in our practicing, and repeat the same things over and over ad nauseum, and… what’s that quote??…

“The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results.”

I’d like to make the case that improvisation skills for classically-trained musicians would alleviate performance anxiety by 59.7%. This number is totally pulled out of a hat, but it drives home the point that if classical musicians had improvisation chops, the music would not only gain a freshness and spontaneity about it, but the performer would have the skills to get back ‘home’ when they’ve strayed.

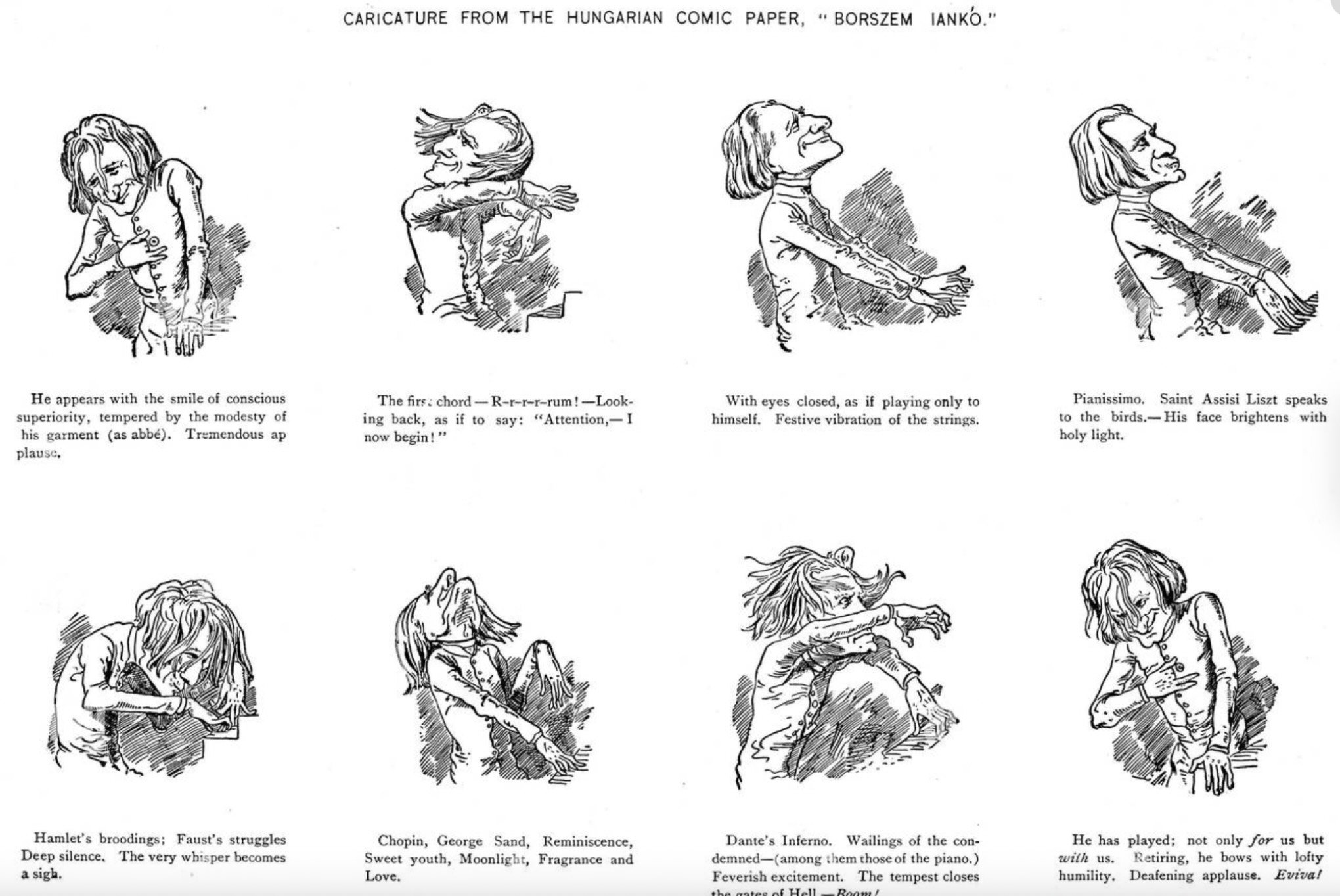

The American pianist Amy Fay wrote in her memoir about hearing Franz Liszt play in the 1870s:

“Liszt sometimes strikes wrong notes when he plays, but it does not trouble him in the least. On the contrary, he rather enjoys it. He reminds me of one of the cabinet ministers in Berlin, of whom it is said that he has an amazing talent for making blunders, but a still more amazing one for getting out of them and covering them up. Of Liszt the first part of this is not true, for if he strikes a wrong note it is simply because he chooses to be careless. But the last part of it applies to him eminently. It always amuses him instead of disconcerting him when he comes down squarely wrong, as it affords him an opportunity of displaying his ingenuity and giving things such a turn that the false note will appear simply a key leading to new and unexpected beauties.”

4. Pharmacological Interventions

Now, speaking of “Elephants in the Room”, let’s talk DRUGS!

Most musicians know about beta-blockers, the adrenyline-blocking pills that were originally intended to only be prescribed to people with heart conditions and high blood-pressure.

It seems to me that the music industry has become much too dependant on beta-blockers, forcing musicians into roles that have just too much of a whiff of dealers and junkies for comfort. Yes, that’s a really strong statement.

I certainly have no issue with suffering musicians turning to pharmacological solutions when anxieties significantly disrupt their lives.

There should indeed be no sense of shame for those musicians who suffer from anxiety disorders getting help from these pills. They can be tremendously helpful and enable musicians a path to regaining their musical expression. Full disclosure: I took beta-blockers throughout the years of injuries and a highly stressful breakdown of my career.

But the music system is depending on these kinds of drugs in a way that is just too reminiscent of the opioid pandemic for comfort. When so many musicians are completely dependant for their livelihoods on drugs, there’s a problem with the system. When drugs are the first and only go-to intervention for addressing a problem, there’s a problem with the system.

Beta-blockers used to be a taboo subject for musicians. In the past 20 or so years, their usage in alleviating performance anxiety has become so wide-spread that I hear of teachers applying pressure on students in conservatories to take them in order to snag the audition (thereby making the teacher look good). While beta-blockers, similar to anti-depressants, can be a life-saver for those with severe anxiety impediments, there is a potential down-side. Many musicians describe difficulties with rhythmic control and a flattening of emotional engagement when taking the medications. Singers and wind-players should be careful in using these medications because of a decreased ability to exert the respiratory system.

The reason I’m being a Poor-Sport-Debbie-Downer here is not only because of the health issues, but also because of the systemic and cultural messages inherent with industry’s dependance on beta-blockers.

Increased dependance on anxiety-controlling substances creates an industry message: Missteps are not to be tolerated; Sterile perfectionism enjoys a higher value than spontaneous exploration; The industry wants more technical precision than heart-filled engagement (beta-blockers literally inhibit the heart, causing it to beat more slowly and less forcefully).

Please know that this is not written to make anyone who depends on beta-blockers for functioning in their careers feel bad. The only intention here is to send out a warning. Please don’t use these substances without being in contact with trusted doctors to explore the benefits and drawbacks from such pharmacological interventions, and please, please, also explore other, non-pharmacological, ways of engaging with the issue of performance anxiety.

I’d like to end this post with a nod to the French pianist Alfred Cortot, who gives a master-class on Robert Schumann’s Der Dichter spricht [The Poet Speaks]. Cortot didn’t shy away from mistakes in his performances. His recordings are peppered with flubs, he was less concerned with technical accuracy and more engaged in the communicative and expressive power of music.

Maybe we can have the courage to step away from the perfection paradigm and explore other aspects of musical communication?

Why not end with a quote of the most perfectly imperfect musician Robert Schumann who suffered so much from his lack of conducting abilities, his social anxiety and performance difficulties.

“I am affected by everything that goes on in the world, and think it all over in my own way…That is why my compositions are sometimes difficult to understand, because they are connected with distant interests; and sometimes striking, because everything extraordinary that happens impresses me, and impels me to express it in music...”